10. Luigi Tarisio, François-Marie Pupunat (or who else)? An enigma in 4 photographs.

If it weren't for the fact that in dealing with the history of Cremonese violin making we inevitably encounter, at a certain point, the controversial figure of Luigi Tarisio, there would be no need to present on this site the enigma that arose nine years ago with the revelation of three photographs.

On May 25, 2015, the article entitled "Tarisio, the Violin Hunter" appeared on the blog Il viaggiatore ignorante.[1] Its author was certainly Giuseppe Teruggi, who declared himself "One of the grandchildren of Teruggi Luigi, alias Tarisio, who... was my great-great-grandfather...".

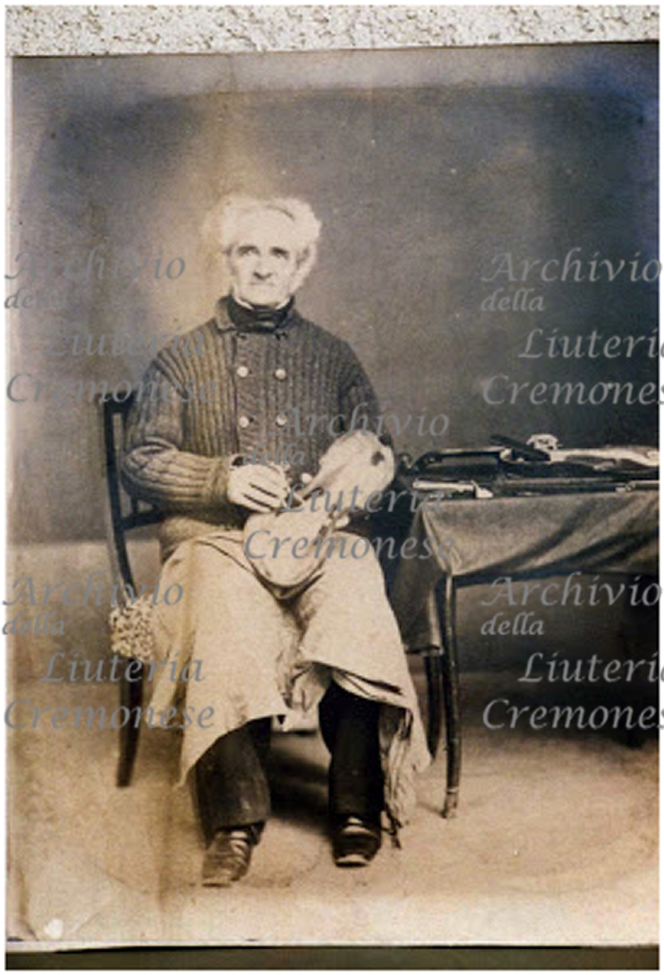

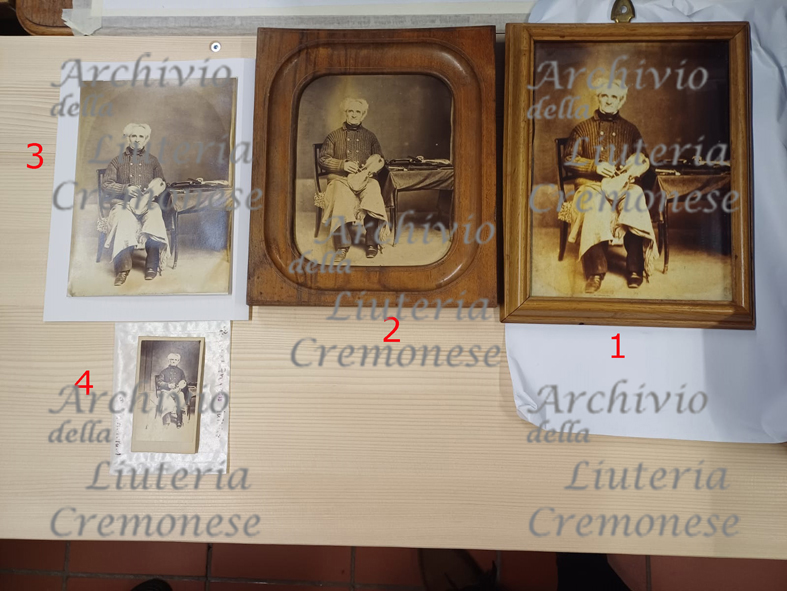

Accompanying the article was the only existing image of Tarisio (no 1), which had remained unknown until then.

1

At that time, the most recent investigation into Luigi Tarisio had been that of Nicholas Sackman – composer and associate professor at the Department of Music at the University of Nottingham – contained in his book The Messiah violin: a reliable history?[2] The author, having reviewed the news reported by the numerous writers who had previously dealt with it (pointing out the ambiguities point by point), laconically stated that "Luigi Tarisio is surrounded by a veritable fog".

On 7 June 2016, the graffitiamilano blog posted a new article entitled “Luigi Teruggi da Fontaneto d'Agogna alias Tarisio, an astute violin collector”, signed by a certain Tony Graffio.[3]

In it, among already known information, we read that: «The Teruggi family of Fontaneto d'Agogna, who had Tarisio among their ancestors, passed on all of their documents to their first-born males as if the papers were the true treasures to be handed down to posterity. The passport, the original photograph taken in Paris, the birth certificate, the letters, the original notarial deeds reporting the purchases made by Tarisio and many other paperwork which I promised to examine carefully and which I plan to publish in September, in occasion of the temporary return to Italy, to Cremona, of Stradivari's most famous violin...».

Among other things, it presented the image of a genealogy of the Teruggi family, which began in 1796 (but essentially without dates), handwritten in a somewhat disorderly manner - perhaps by family members - on a squared sheet of paper, in which Tarisio appears without descendants, contradicting Giuseppe Teruggi, who in the 2015 article because in reality Tarisio was not his great-great-great grandfather, but rather his great-great-great uncle.

No substantial news regarding Tarisio led Renato Meucci to the book The Absolute Stradivari - the Messie violin 1716/2016, published by the Violin Museum of Cremona on the occasion of the exhibition dedicated to the instrument preserved at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, in which it was shown new, courtesy of the heirs, the photograph of Tarisio. While Tony Graffio's promise to publish the Teruggi family documents 'in September' was not kept.

The following year, in his extensive and implacable review of the aforementioned Cremonese book, Sackman also regretted the failure to publish the documents of the Teruggi family, noting that «Evidently the owner of the family’s ‘original documents’ didn’t think that contacting Cremona’s Museo del Violino in advance of the Messiah exhibition (September-December 2016) might be a more appropriate strategy.»

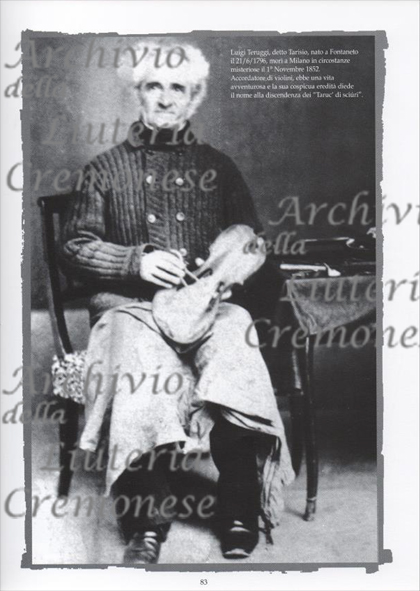

The English author also noted, in his review, that one of the photographs of «‘unidentified old man’, [… published by Tony Graffio, has] a caption printed in the top-right corner of the image; the first part of the caption can be deciphered: ‘Luigi Tarisio, detto Teruggi, nato a Fontaneto il 21/6/1796, mori a Milano in circostanze misterioso il 1 Novembre 1852’ (… died in mysterious circumstances 1st November 1852). The photograph is seemingly a page from a published book (the page number – ‘83’ – can be seen at the bottom of the photograph) but no identification of the book [or, perhaps, of a magazine].is provided and this reviewer [Sackman] has not been able to locate the book. [...] the unidentified old man in the photograph – the supposed T/T – appears to be rather short in stature (the Hills describe Tarisio as ‘tall and thin’) and T/T looks to be at least 65 years of age. If T/T was born in 1796 then he was 56 years of age when he apparently died in 1852 (but the second web-blog states that T/T was 60 years of age when he died which, if he was born in 1796, would place his death in 1856).» Finally, Sackman warned that «Since the present review was first web-published the ‘old man’ in the photograph, ‘sitting on a low chair’, has been identified as the violin-maker Francois-Marie Pupanat [sic] (1802-1868.»[4]

The fact is that the numerous contradictions in Tarisio's biographical information had created a lot of confusion, starting from doubts about Tarisio's kinship with the Teruggi family, which was however known. since 1857. to Ignazio Cantù, who in a communication made to the Accademia Fisio-Medica-Statistica of Milan, had written: «This violin [Messiah] was part of the many bowed instruments that Terruggi's heirs sold, from what we are assured, for around 40,000 francs to Mr. Vuillaume; and among which were others of first merit by Stradivari himself and some by the Guarnerio del Gesù, which Terruggi had bought many years ago from the Milanese nobleman Giacomo de Carli.»[5]

And also that the place where Tarisio's relatives lived was Fontaneto d'Agogna, in the province of Novara, and not Fontaneto Po, in the province of Vercelli, as many authors have written until recently, Antoine had specified since 1876 Vidal, when he wrote that J.B. Vuillaume, having learned the news of Tarisio's death, «…does not hesitate. Having immediately come into contact with the family of the deceased, he left for Italy on 8 January 1855. Having arrived in Novara, he was taken near 'Fontenette' [sic], to the Croce farm, a small property that had belonged to Tarisio, where finds the heirs reunited...».[6]

Alessandro Restelli in his book Il mercato antiquario di strumenti musicali a Milano, published in the same year as Sackman's review, after having once again reviewed the bibliography concerning Tarisio in an even more analytical and complete manner than Sackman, and based on the typescript unpublished research by Laura Marcolini from 2001,[7] has finally documented once and for all the year of Tarisio's birth, citing the baptismal certificate, preserved in the parish of Santa Maria Assunta in Fontaneto d'Agogna: «Aloisius Terugio - Anno Domini Millesi.mo Septingente.mo Nonage.moSexto die Vigesima prima Junij ego Franciscus Antonius Imbricus hujus Ecclesia Beata Maria Vergine Assumpta Fontaneti Archipresbiter baptizavi infantem die eadem natum ex Josephi Maria Terugio Fili Philippi et Maria Dominica Barbaglia filia Josephi conjugibus hujus Parochia, cui impositum fuit nomen Aloisius. Patrini Johannes Dho filium Antonij, et Maria Francesca Cerri filia Silvani uxori Isidori Terugio ambo huius loci. Et pro fidelis Archipresbiter Imbricus.», The author also clarified the date of death, publishing the certificate from the registration made in the Official Gazette of Milan on 4 November 1854, p. 1331, which reads: «Died in Milan on 1 November 1854 over the age of 7 […] Tarisio Luigi, 60, violin maker, 2118» (the number indicated at the end was the street number of the house where Tarisio lived near Porta Tenaglia, and the number 60 represented his age, which, naturally, if he was born in 1796, in 1854 was 58 years old).[8] The Extract from the Parish Registers for the Death Certificates from the day 'first 9bre to the whole Year 1884', of the Parish of San Simpliciano in Milan, recently consulted, confirms - in Table 80 - the death of Luigi Tarisio, registered however as Teruggi: « 3 │ Teruggio Luigi │ age / 60 │ State / Unmarried (sic) │ Homeland / Novara │ N. Civic / 2118 │ Paternity / Giuseppe / Maternity / Barbaglia Maria │ Day / 1- 9bre.» The ecclesiastical document is important because it registered Tarisio with the surname of origin and the names of the parents reported in the baptismal certificate, thus confirming his kinship with the family of Fontaneto d'Agogna.

In 2021, the Genially Education blog posted a team effort, created to enhance the history and attractions of Fontaneto d'Agogna, in which a section was dedicated to Luigi Tarisio, which also provides news and images regarding his heirs Teruggi,[9] and also included a new reproduction of the photograph of the alleged Tarisio already published previously, in which part of the wooden frame that encloses it can be seen on three sides.

1

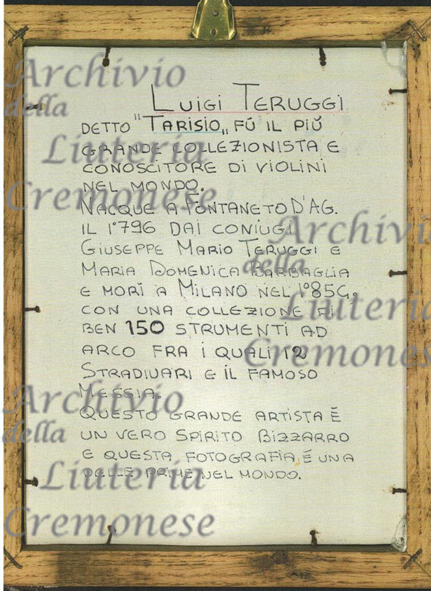

A descendant of the Teruggi family confirmed that photograph no. 1, of which he kindly provided the reproduction shown here, is kept by relatives and is framed and protected by glass (never opened to avoid the risk of ruining it). Behind the small picture is a handwritten sheet of paper with the following inscription, written in recent times by Giovanni Platinetti, a descendant of Gaudenzio, one of Tarisio's three brothers: “LUIGI TERUGGI, CALLED TARISIO, WAS THE GREATEST COLLECTOR AND CONNOISSEUR OF VIOLINS IN THE WORLD. HE WAS BORN IN FONTANETO D’AG. N. 1796 TO THE SPOUSES OF GIUSEPPE MARIO TERUGGI AND MARIA DOMENICA BARBAGLIA AND DIED IN MILAN IN 1854, WITH A COLLECTION OF 150 STRING INSTRUMENTS INCLUDING 12 STRADIVARIANS AND THE FAMOUS MESSIA. THIS GREAT ARTIST IS A TRUE BIZARRE SPIRIT AND THIS PHOTOGRAPH IS ONE OF THE FIRST IN THE WORLD.” The family recounts that the photograph was taken in Paris in 1853, and also that the sweater worn by the photographed person was kept in the house for many years and was lost over the last few decades.

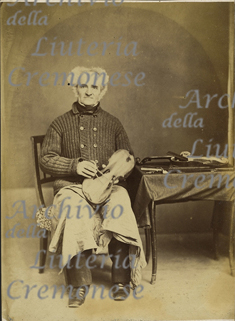

Photo No. 1, 23 x 18.1 cm, is supposed to be an albumen print and shows a mature man with thick white hair, wearing a wide-rib wool sweater with double buttons, dark trousers and leather shoes. He is sitting on a 19th-century chair in vague Biedermeier style, with the seat covered with a floral cloth, and on his lap he is holding a large light-coloured cloth, on which he is resting, held in his left hand, showing its inner face, the soundboard of a violin, on which rests a compass held in his right hand.

Next to the character, on the right, we can see a portion of a small table/desk covered by a cloth, the legs of which vaguely recall the Louis XV style, on which some objects are placed: in the background, a violin without its soundboard (the one in the character's hand?) is clearly visible, with a fingerboard and a cello bridge on top and a white shape that looks like a 'blank' violin neck, while in the foreground there are some other indistinct tools, among which, however, a small violin maker's plane is clearly recognisable.

The place where the shot was taken looks like a photographic studio; the back wall, except for a bright spot behind the character's head, is uniformly dark and has a high, lighter plinth at the bottom; the floor also appears uniform and shows no notable details.

The descendant with whom he is in contact has made it known that photograph no. 1 would be one of the three donated by Tarisio to his three brothers: Gaudenzio (1798-1887), Francesco (1807-1861), Pietro (1811-1887). The heirs, in fact, kept a second framed copy [no. 2] of 20.1 x 16.1 cm, in which the other two legs of the table can be seen on the right, while a third photograph that was in the hands of the descendants would have been sent in 1953 to the editorial staff of the Corriere della Sera in Milan to accompany an article, which was not published, and was never returned.

2

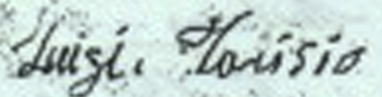

From the passport of Luigi Tarisio, cited above, issued by the Turin Police Headquarters in 1853 and renewed in 1854, it is clear that it was valid for “all the States of the Monarchy … (?), those of Italy, Germany, Switzerland, France, Holland and Austria”. The document reports the features of the holder as follows: “Age 54 (sic) / Height 1.71 m / Mixed hair / Dark eyebrows / Brown eyes / Medium forehead / Mixed brown beard / Natural complexion / Condition Musical instrument repairer” and also the autograph signature of Tarisio.

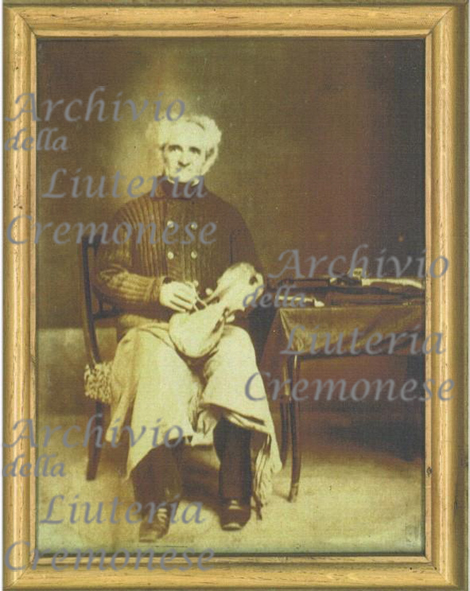

Since its publication in 2015, photograph no. 1 has been reproduced several times online and in paper publications on violin making as a portrait of Luigi Tarisio, except that, in the same year, a similar photograph (no. 3) portraying the same character was found in the laboratory collection of the violin and bow maker François-Marie Pupunat (1802-1868) from Lausanne, acquired by the Musée Historique of the Swiss city through a descendant of his still living in Écuvillon (France).

Pupunat was born in this French village near the Swiss border, not far from Geneva, and was the son of modest peasants. He had learned the trade of carpenter-cabinetmaker in his youth and, when in 1823 a favorable draw spared him five years of military service, he would leave for a journey to Italy that lasted four years. "The passport issued to Pupunat in 1823 when he was 20 years old describes him as 1.74 m tall, with a covered forehead, black eyebrows, beard and eyes, an aquiline nose, a medium mouth, a round face and chin, and a fair, brown complexion."[10] Upon his return home in 1827, he married and settled in Lausanne, where he spent the rest of his life, first working as a carpenter and then gradually converting to violin making, probably – it is said – through the intermediation of a rich collector, Joseph von der Weid de Römertzwill, who gave him several instruments to repair and led him to learn his new profession as a self-taught. Pupunat officially became a violin maker in 1836 and built about 350 instruments, presenting some of them at important exhibitions, earning the respect of his fellow citizens in other fields as well.[[11] Left childless and having not trained a successor, his workshop was liquidated upon his death.

The Pupunat collection of the Musée Historique in Lausanne includes an authenticated violin in its case and various accessories, medals and certificates, professional and personal archives (correspondence, account books, inheritance documents, etc.), identity documents, a snuffbox and, indeed, the aforementioned photograph no. 3.

3

André Schmid, Portrait du luthier François-Marie Pupunat, photographie, vers 1864, coll. Musée Historique Lausanne

© Atelier de numérisation Ville de Lausanne.

This photograph (P.1.P.1.Pupunat Franç.001), 20.5 x 15 cm, is cataloged as «Portrait of the luthier François Marie Pupunat placing his hand on a violin table» and is a photographic positive printed on albuminated paper glued onto cardboard, which does not it has inscriptions or particular signs neither on the obverse nor on the reverse,[12] and has no negative.

It differs from photos 1 and 2 of the Teruggi heirs for the shadow in the background, which is arched, and for the almost complete view of the table/desk next to it, of which all four legs can be seen as in number 2.

The context in which photograph no. 3 was found justified the attribution by the cataloguers of the Lausanne Museum of the identity of the violin maker F.M. Pupunat to the subject of the portrait, who was most likely its owner, while the shot, dated around 1864, was assigned to the Lausanne photographer André Schmid (1836-1914), also because a similar photograph (no. 4), in “Carte de Visite” format, is preserved in the collection of this photographer[[13] in the same Museum.

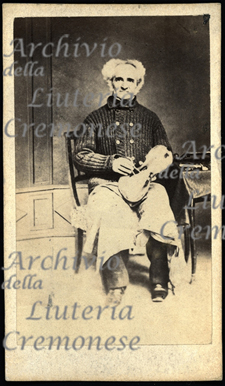

4

André Schmid, Portrait du luthier François-Marie Pupunat, photographie, vers 1864, coll. Musée Historique Lausanne

© Atelier de numérisation Ville de Lausanne.

Photograph no. 4 (P.2.D.3.1.A.1.Pu.1) is a silver monochrome positive printed on albumen paper (8.8 x 5.3 cm) glued onto cardboard (10.2 x 5.8 cm), without any marks or brands on either the front or the back, unfortunately this one also lacks the negative; the date of the shot is also fixed in this case at around 1864 by the photographer Schmid.[14]

It represents the same character, in the exact same pose as the two photographs described above, but with a larger portion of the floor in front of the feet, a larger portion of the background on the left and a smaller part of the table on the right; it shows on the plinth and on the back wall on the left some squares of lines and diamonds that are not seen in the photographs illustrated above. The shadows in the photograph would not seem to coincide, because the light on the subject and on the table seems to come from the top-top right, while the shadows of the decorations on the wall are drawn as if the lighting came from the top left: the rhombus on the right has an accentuated shadow different from that of the rhombus on the left and the column and could have been drawn with a retouching on the plate. Undoubtedly, however, the negative of this photograph, which was most likely cropped after printing to fit the “Carte de visite” format, should have been the original and contained the portions of the image missing in this print but which are visible in the larger format photographs 2 and 3.

It is known that at the time photographs were contact printed, that is, by placing the negative on photographic paper, and the possibility that the larger format photos may have used the negative of a second shot is excluded by the fact that the pose of the photographed character is identical in all three photographs, and since the long exposure times forced the subject to remain still, it is impossible to believe that he could have assumed the exact same position at different times.

The known copies of the photograph are therefore four and all of different formats: (n. 1) 24 x 18.1 cm and (n. 2) 20.1 x 16.1 cm from Fontaneto, (n. 3) 20 x 15 cm and (n. 4) 10.2 x 5.8 cm from Lausanne. The differences in format suggest that photo no. 1 of Fontaneto could not have been printed with the same negative as photos no. 2 (Fontaneto) and no. 3 (Lausanne) - which appear to match -, while they could, perhaps, have been taken from the negative of the “Carte de visite” format (no. 4) of Lausanne, but to do this the photographer would have had to use an enlarger (which at the time had only been invented, was enormous and worked only with sunlight, with long exposure times, and which not all photographers owned and were able to use) and the photos would have had to be retouched during printing to erase the squares and modify the backgrounds.

At this point it is honest to ask yourself some questions:

What is the possible date of the shot, considering that the “Carte de visite” format was patented in Paris in 1854 by André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri (although it was already known) and entered into common use in 1859?

It must be considered that Luigi Tarisio died on November 1, 1854 and it is right to ask, beyond the apparent age of the photographed subject, whether this date can be compatible with that of the possible shot. Admitting that it was taken – as believed by the Teruggi heirs – in 1853 in Paris poses some problems, which would not instead arise for F.M. Pupunat, as he died on April 9, 1868 at the age of 66.

Where was the shot taken and who took it?

The Lausanne Museum, as mentioned, has identified the author as the photographer André Schmid, whose collection also includes numerous “Carte de Visite” format photographs and negatives taken four at a time on the same plate, demonstrating that he had a camera suitable for this purpose.

Who is the character portrayed?

At the current stage of the investigation there is no certain evidence that would support the recognition of one, the other, or any other identity.

The answer to these questions will be very complex in any case, because until the fortunate eventuality of finding the original negative (provided it has been preserved) in the collections of some photographer of the time, or another print in one of the very popular collections of “Carte de visite” format photographs, it will not be possible to determine with certainty either the origin of the shot, nor its author, nor the identity of the person.

Whatever the outcome of the research, there is no doubt that the Lausanne Museum, as a cultural institution, could review – if necessary – its decisions, while it is likely that the Teruggi heirs will be more inclined to strenuously defend the attribution of the photo portrait to their ancestor.

On the other hand, this attitude has an illustrious precedent in the history of violin making: Giacomo II Stradivari († 1901), descendant of the famous Antonio and a merchant in Milan, in his reply to a letter sent to him in 1892 by Alfred Hill, who had questioned him on the subject, had obstinately defended from contrary hypotheses the identity of the character depicted in a painting which, kept in the Stradivari family in Cremona for time immemorial as a portrait of their famous ancestor, had been sold to J.B. Vuillaume and by his heirs sold to the Hill family.[15] The painting, which arrived in 1952 at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, is cataloged there as "Portrait of a Musician by Anonymous Italian-Cremonese (c.1570/90)".[16]

Gianpaolo Gregori

May 7, 2024

We thank Alfio Angiolini, Roberto Caccialanza, Sergio Cantoia, Nathalie Lüginbühl-Blaser and Roberto Regazzi for their help.

_______

[1] https://www.viaggiatoriignoranti.it/2015/05/tarisio-il-cacciatore-di-violini.html

[2] Nicholas SACKMAN, The Messiah violin: a reliable history?, Nottingham, 2015 e 2020, pp.

[3] https://graffitiamilano.blogspot.com/2016/06/luigi-teruggi-da-fontaneto-dagogna.html

[4] https://www.themessiahviolin.uk/AbsoluteStradivariReview.pdf

[5] Ignazio CANTÙ, «SULLE SCUOLE ARTISTICHE ISTRUMENTALI ITALIANE - MEMORIA del Socio Ordinario Segret. IGNAZIO CANTU', Letta nella seduta del giorno 23 aprile 1857», in: Atti dell’Accademia Fisio-Medico-Statistica di Milano – Anno Accademico 1856-1857, Milan, Stabilimento Tipografico del Dott. Pietro Bonietti, 1887, p. 268, nota 2.

[6] Antoine VIDAL, Les Instruments a archet …,T. Premier, Paris, Imprimerie de J. Claye, 1876, . pp. 123-124.

[7] Laura MARCOLINI, Luigi Tarisio, unpublished manuscript2001.

[8] Alessandro RESTELLI, ll mercato antiquario di strumenti musicali a Milano fra Ottocento e Novecento, Milan, L.E.L., 2017, p. 29.

[9] https://view.genial.ly/602a428e55c6b00d538c695d/interactive-image-fontaneto-dagogna-terra-dacqua-e-memoria

[10] See: L. M., «Les violons de Lausanne», in: Conteur Vaudois, Journal de la Suisse Romande, n. 41, 5 ottobre 1867.

[11] https://museris.lausanne.ch/SGP/Consultation.aspx?Id=7967

[12] https://museris.lausanne.ch/SGP/Consultation.aspx?Id=10753

https://www.lausanne.ch/apps/museris/?artistes=Schmid%2C%20Andr%C3%A9&page=164&id=136968&sort=auteur

[14] W.H., A.F. and A.E. HILL, Antonio Stradivari His life and work (1644-1737), London, Hill, 1902, p. 279.

[15] https://www.ashmolean.org/collections-online#/item/ash-object-372464